Preview

Creation Date

1997

Description

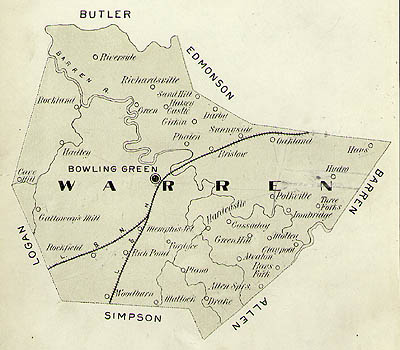

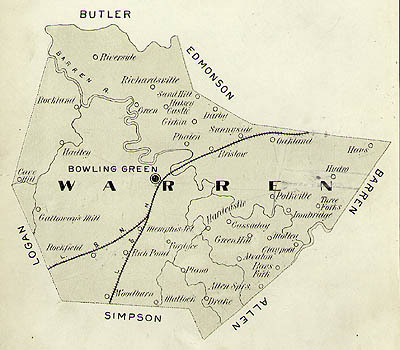

Warren County embraces a 547 square mile area in south central Kentucky's Pennyroyal Region. The Big Barren River flows through the county and empties into the Green River, which provides the county's northwest border. The county is transected by Interstate 65, the William H. Natcher Parkway (formerly Green River Parkway) and by CSX Transportation (formerly Louisville and Nashville Railroad line).

A fertile, gently undulating area, the county's major agricultural products include tobacco, corn and other grains and live stock. The county's 1994 population was estimated at 83,000; its largest communities include Woodburn (population 300), Smiths Grove (population 800) and Bowling Green, the state's fifth largest city (population 45,500).

Bowling Green, the county seat, boasts a number of major industries including General Motor's Corvette Plant, Holley Replacement Parts, Eaton Corporation, James River, International Paper, Eagle Industries, County Oven Bakery, DESA International, Hill Pet Nutritions and the corporate offices of Fruit of the Loom. Bowling Green is also the home of Western Kentucky University, a state supported institution that offers a broad spectrum of educational programs. Of special interest to historians and genealogists is the university's Kentucky Library that houses a fine collection of materials concerning the commonwealth and its people.

Created in 1797 from a portion of neighboring Logan County, Warren was the state's 24th county and was named for Boston's Dr. Joseph Warren, a hero of the Battle of Bunker Hill. Because few records were kept or have been preserved, little is known about the earliest explorers and initial settlers in the Warren County area. A group of a dozen or more "long hunters" apparently camped along the Barren River in the early summer of 1775 and carved their names and the date on a couple of large beech trees. Hunters and explorers who followed Indian trails from the eastern and northern portions of Kentucky to Middle Tennessee often crossed the Barren River at a shallow spot near the present I-65 bridge. Unfortunately, few of these visitors left accounts of their experiences. When Kentucky achieved statehood in 1792 an undetermined number of settlers inhabited the area. Four years later, when the region south of the Green River opened to Virginia's Revolutionary War soldiers, land hungry families from the eastern seaboard poured into the area. Many of the new residents held land warrants that granted acreage in payment for military services. Others had purchased warrants or land from veterans. More than a few were squatters.

Newcomers generally staked claims along water courses and in heavily forested areas that provided building supplies and fuel, avoiding the "barrens," a crescent shaped, woodless region extending from the present areas of Glasgow, Bowling Green, Franklin, Guthrie, and Hopkinsville. Residents soon discovered that the barrens' soil was rich, not thin and poor as originally supposed, and concluded that perhaps the Indians had periodically burned the land to prevent forestation and encourage the growth of vegetation that attracted game.

As the population grew, the need for local government increased. In December, 1796 the state legislature approved a petition to create a new county from the north east portion of Logan County. At their first meeting, the newly appointed Warren County commissioners swore in the officials necessary for the orderly government of the area. At subsequent meetings they set tavern rates, approved the construction of several mills, and called for the clearing of roadways to link all portions of the county. In the summer of 1797 the county officials arranged for the construction of a twenty by twenty-four foot, one-and-a-half story log courthouse and small log jail. Both buildings stood in the middle of the county and about one-and-a-half miles from the river banks; Charles and Robert Moore donated the two acre plot on which they were constructed.

The following March, when the commissioners met in the new courthouse they proposed the creation of a town to surround the public buildings. The Moores donated 30-40 acres for the settlement and, according to the meeting's minutes, the town would be "called and known by the name of Bowlin Green." The extant records give no clues as to who chose the name or why. An early explanation, published about 1900, indicates that the name of the town, like that of the county, saluted patriots of the American Revolution who had pulled down a statue of King George III that stood in New York's Bowling Green Square and used the metal for bullets with which to fight the British.

Following its creation, a surveyor mapped a town around the tiny courthouse and jail. In May, 1799 the first town lot (east half of Park Row) sold for $18, but other sales were slow. Americans were a rural people and south central Kentucky attracted farmers seeking cheap, fertile land. Nevertheless, within a decade the lots immediately adjacent to the public structures had been purchased and a few of them divided and subdivided. Because money was scarce, deeds apparently served as a medium of exchange and some lots changed hands many times before anyone built on them. By 1810, however, a few stores, a brick tavern, and several modest homes faced the square, and the federal census taker listed 23 households with a total of 98 white and 56 slave residents in Bowling Green. In January of 1812 the state legislature passed an act for the "regulation of certain towns," including Bowling Green, and determined that the responsibility of the town's well being rested in the hands of five trustees, to be elected annually by the white male inhabitants. At their initial meeting, the trustees selected one of their members as a presiding officer and another to act as secretary.

The honor of being designated the "county seat" involved a half-decade battle between Bowling Green and the non existent settlements of New Town and Jeffersonville that speculators intended to create on the banks of the Barren River. Eventually the legislature specified Bowling Green and in 1816 the county commenced construction of a fine brick courthouse on the square of land around which the town developed.. In 1821 the Bank of the Commonwealth established a branch office on the square and by 1827 the town boasted a locally owned newspaper, a resident physician, a private school for boys (a school for girls opened in the Presbyterian Church in the mid 1820s), a Masonic lodge, at least one church, two tiny hotels, a number of mercantile shops and an array of other business establishments. Most structures housing a commercial venture also served as a residence for the owner. The courthouse provided meeting space for congregations without buildings and numerous rural log structures provided space for both school and church meetings. A stagecoach line connecting Bowling Green to Louisville, Nashville and Hopkinsville rumbled into town three times a week to discharge and pick up the mail and passengers. The round trip between Bowling Green and Louisville (180 miles) took three days and cost $12.

From its inception Warren County's residents depended on the Barren River as an avenue for commerce. In the winter when the river was high, flatboats loaded with tobacco, ham, whiskey and other farm produce began the arduous trip from a warehouse on the river's edge to New Orleans. The flatboat journey down river and return by wagon or on foot (steamboats did not paddle up the Mississippi and Ohio until after 1814) required about six months. Goods not produced locally came by wagon from Louisville or Nashville on roads that were little better than an animal path, an erratic and expensive mode of freighting.

After the advent of the steamboat on the Ohio River, local businessmen urged that the narrow, winding, snag-filled Green and Barren rivers be improved sufficiently for steamboats to ascend to Bowling Green. Without such river trade, warned a newspaper editor, "we can never be independent or prosperous." Discussions and delays followed but eventually a company of young volunteers cleared the worst snags and overhanging trees. In January 1828 a tiny, single stack steamboat, the United States, arrived at Bowling Green and its cargo of a few boxes of sugar, tea, coffee and other items was unloaded and displayed on the river bank. A local miss later recalled that she could not believe that so much could ever be consumed by the town's residents.

During the 1830s the state authorized improvements on the Green and Barren and eventually provided for the construction of locks and dams. On the completion of these projects, paddle wheelers could ply upriver to the Bowling Green boat landing. To facilitate transportation between the wharf and the center of town, James Rumsey Skiles and Jacob Van Meter organized a stock company to construct a tramway they named "Portage Railroad." Completed in the mid 1830, mule drawn wagons carried passengers and goods from the river to a small depot near the site of the present courthouse on Tenth Street.

Prior to the 1830s Russellville was the most prosperous and populous town in south central Kentucky. With the genesis of steamboat travel, however, Bowling Green assumed a role as the area's commercial center and the town's growth reflected her economic importance. In the 1850s the Louisville and Nashville Railroad Company laid tracks through Warren County and built depots in Bowling Green, Smiths Grove and Woodburn. Opened in October 1859, the last portion of the L&N Railroad line was constructed around Bowling Green; on completion of the job, many of the German and Irish immigrant laborers remained and established homes. In an area that had been settled by Protestant natives of Virginia, Pennsylvania and the Carolina, these Catholic newcomers added a new facet to the south central Kentucky character. A tremendous stimuli to the economy, the railroad nevertheless compromised the community's safety during the Civil War, for the Bowling Green-Warren County area controlled a vital link between Union Kentucky and Confederate Tennessee and other southern states.

War clouds appeared on the horizon in 1860 as the nation divided over the states rights and slavery issues. Most Warren countians opposed secession. Numerous residents, including attorneys and former congressmen Joseph and Warner Underwood campaigned for Constitutional Union candidate John Bell of Tennessee and against Abraham Lincoln, a Kentucky native whom they saw as an uneducated upstart and a danger to the Union's preservation. They also worked to hold the commonwealth in the Union. Throughout the summer of 1861 Kentucky's refusal to choose sides gave temporary respite. But as the state's neutrality melted away in the warm rainy days of late summer, both belligerents talked of controlling the Bowling Green area, for the town guarded the major avenues--the river, roads and rails--to and from the Kentucky-Tennessee border. On September 18 the first group of Confederates arrived at the Bowling Green depot; eventually about 20,000 southern troops camped along the waterways of Warren and adjoining counties. Following the arrival of the initial troops, a young Unionist recorded in her diary, "The Philistines are upon us."

During their five month occupation of the area, the southern army experienced a frustrating stay. Believing that the county's 17,000 residents were sympathetic to the southern cause, the Confederates soon discovered the denizens were three-to-one pro Union. Thus, they encountered considerable hostility and acquired few recruits. Persistent rumors incorrectly told of large numbers of enemy troops pushing into central Kentucky. The soldiers fortified the town's high spots and prepared for a big battle. But illness, not a Union army, was the foe that felled the secesh troops. Measles, typhoid, dysentery, influenza, scurvy and pneumonia thinned their ranks. More than one-tenth of the Confederates died and hundreds of others languished in makeshift hospital facilities that were inadequately provisioned and staffed.

In late November, after a provisional convention at Russellville proclaimed Bowling Green the "Confederate capital of Kentucky," the Confederate governor and his council attempted to establish their government and the legislature convened for a brief time at Bowling Green. None of them, however, had any authority beyond the CSA's shrinking military lines. The distinction of "capital" was a fleeting honor, and following Confederate defeats at Mill Springs (in Eastern Kentucky near the Cumberland River) and Columbus (on the Mississippi River) as well as the southward advancement of Federal troops from Louisville, the Confederates decided to pull back to Nashville. The retreat began on February 11 and the last troops left Warren County on Valentines Day. As they withdrew amid freezing rain and snow, an advanced group of Federal troops arrived on the north side of the Barren River. Unable to cross because the foot and railroad bridges had been destroyed, they lobbed a few shells towards town and the following day crossed the river upstream near and entered Bowling Green.

For a brief period a sizable Union army remained in the area, but by mid spring most of the soldiers had moved south. Large armies enroute to and from Tennessee passed through from time to time and although the town remained under martial law until after the war's end, only a few hundred troop garrisoned the area. Composed of more Yankee than Kentucky Unionists, the troops patrolled the countryside that seemed plagued with guerrillas, maintained a hospital in town and apparently viewed area residents as disloyal rebels. In the final year of the hostilities the army inducted more than 2000 black troops at Bowling Green's recruiting center.

The lengthy federal occupation stirred up deep-rooted animosities and fears. An officer from Christian county stationed in Bowling Green during the hostilities' final months probably expressed the sentiments of many residents when he wrote:

I wish the rebels were whipped I wish the cursed Yankees were out of the country. No good feeling has grown out of their occupancy of our state, but a dissimilarity of the most striking is manifested in the way they feel and think. . . . I must say I greatly prefer our own way.

Union or Confederate, the presence of soldiers for more than four years--the last troops left the area in 1867--drained the county of its resources. Troops of both sides bivouacked in orchards, drilled in clover fields, cut down trees, burned fences, stole livestock and horses, requisitioned food and forage (or paid with worthless money or IOUs). They also looted hen houses, smoke houses and vegetable cellars; wore out or destroyed roads and bridges; created frightening sanitation and health problems; violated civil rights and infringed on the dignity and serenity of civilians. At the war's onset the majority of area denizens had been pro Union. Nevertheless, nearly every family had at least one member in each army. The strain of divided sentiments, the loss of loved ones, the destruction of property and the indignities of real or imagined ill treatment created bitterness that remained long after the shooting stopped. Bowling Green's residents, like other Kentuckians, became more "southern" after the war than they had been before it.

Warren County emerged from the Civil War in a sorry plight. Although the majority of residents had been loyal to the Union, the victorious Federals had treated them like foes. Martial law and the suspension of habeas corpus remained in effect for six months after the war's end, and from 1866 until 1870 the efforts of the Freedman's Bureau to help blacks stirred racial antagonisms. Physical alterations were also apparent. The railroad depot lay in shambles, the streets and roadways were riddled with potholes, becoming impassable quagmires in damp weather. During their evacuation, the Confederates destroyed bridges over the Barren River. The Union army had repaired the railroad bridge, but the footbridge had merely been replaced with a pontoon.

Road repairs started in earnest and a new covered footbridge eventually spanned the Barren. A magnificent three story brick and stone courthouse, which cost $125,000 and was financed by private subscription, opened in 1868 and became a great source of pride. A picturesque little park with a bubbling fountain and reflecting pool replaced the dilapidated 1816 courthouse in the square.

During the post war years the railroad assumed major economic and thus political importance to the county. Bristow, Smiths Grove, Woodburn, communities that formed along the line, built passenger and freight depots and the availability of relatively cheap freight boost the profits of area farmers. Among the state's 116 counties in 1870, Warren ranked fourth in the production of hogs,. fifth in wheat and seventh in corn and cattle. Sixth largest in population, the county's taxable property ranked 10th, almost double that of thirty years earlier. The tonnage of livestock increased more than five fold during the 1890s, and strawberries as well as other food stuffs became important cash crops for area farmers and profitable commodities for merchants who supplied Warren county foods for distant kitchens.

Carloads of barrel staves and tool handles also went to big city manufacturers. Gleaming white limestone, nature's most elegant building material, was quarried in the county, fabricated in the town's stone mills and shipped by rail to urban areas. Between 1880 and the 1920s local stone companies filled orders for hundreds of structures, including the Kentucky Governor's Mansion in Frankfort, Presbyterian Theological Seminary and Sacred Heart Academy in Louisville, and public and private edifices in Boston, New York, Atlanta, District of Columbia and other metropolitan areas.

Building projects at home also utilized local materials. Although some log building continued to serve as homes and county structures, the popularity of stone and brick increased. Fences of cut stone became status symbols. In the 1870s city folk benefited from the introduction of piped gas and water and the telephone became popular in the 1880s. The decade also witnessed the introduction of the state's public school system and by the mid 1880s the city boasted two modern brick schoolhouses--an elementary school for white children and a smaller structure for the town's African American youngsters. The nearly two dozen rural one-room log or frame schools continued in use and were gradually replaced over many decades. Consolidation in the 1950s weeded out the last of the substandard structures. The curriculum for all public schools included the 3 Rs; but a few schools also offered classes in music, art, composition, speech and spelling.

The public school system did not provide secondary educational opportunities until after 1910, although several private schools offered fine educations for those who could afford them. Ogden College (1871-1928) for men and Potter College (1886-1908) for young ladies opened on adjoining campuses on Bowling Green's southern perimeter; Woodburn's Cedar Bluff Female College began in 1866. (Despite their misleading titles, these institutions were high schools equivalents, not comparable to modern colleges). In 1884 the Southern Normal School and Business College moved from Glasgow to Bowling Green and conducted both academic and commercial programs. In 1906 the state legislature created two state normal schools, one of which was the academic portion of the Southern Normal School, renamed Western Kentucky State Normal School. Two years later the institution's president, Henry Hardin Cherry, purchased the defunct Potter College and moved his school to its hilltop campus. The Business College, sold to private investors, achieved a reputation for excellence and was absorbed by Western in the 1950s. In 1966 Western achieved university status.

Temperance was a pressing question in the decade preceding World War I. Church and social groups pushed for local options and then campaigned for a temperance law. Led by area women, prohibitionists organized parades and carried signs urging men (women could not vote) to cast YES ballots. For a brief period Warren County went dry. Prohibition remained an explosive issue until the passage of the Volstead Act in 1919.

The years between 1900 and 1915 were halcyon ones for many residents who seemed blissfully unaware of war clouds gathering in Europe. Yet, when the call to arms came in the spring of 1917, they responded with gusto. About 1000 young men served in the armed forces; four earned Distinguished Service Crosses, two were awarded the Croix de Guerre and many received citations for bravery in battle. Forty-nine gave their lives. Several area women joined the Red Cross and served in Europe and others supported the liberty loan drives and volunteered for Red Cross activities at home. To finance their war-related endeavors, local women held parades and bake sales and operated a country store at the county fair. The most unique money making scheme, however, was to place workers at the warehouse during tobacco season and have them solicit a hand of tobacco from every wagon load. Area farmers cheerfully responded to the pleas and this tobacco brought top prices and swelled Red Cross coffers.

The decades between the two world wars witnessed many changes. The automobile emphasized the need for better roadways and lessened the distinction between the advantages enjoyed by urban and rural dwellers. Cars also increased the demand for oil, and during the 1920s speculators, drillers, and oil company representatives flocked to the area to pump black gold from Warren County's shallow wells. The boom stimulated every industry, from hotels to dry cleaners. Housing was at a premium; many workers who came to the area during the boom lived in out-buildings and even tents. Some made fortunes but more merely increased their misery. The deaths of two children from malnutrition and exposure in their family's inadequate quarters on the outskirts of Bowling Green encouraged a number of area women to organize relief programs. To provide care for the destitute, they founded a county welfare home and funded their activities through bazaars, fiddling contests, football games, plays and concerts. A number of women's clubs also held story-telling hour for small visitors, and other groups provided camp scholarships for summer fun. When the depression struck the nation a few years later, Warren County already had in operation the nucleus of a social service program.

The Depression years witnessed important building projects. Funded by the WPA. Cherry Hall and the Kentucky Building on the college's campus, a new jail near the courthouse and the city's sewer system provided work for area residents. The post office received an annex, two new tobacco warehouses opened, and in June, 1940 WLBJ radio station went on the air. As part of the federal defense program,. the national government appropriated $334,000 for a municipal airport. Yet, despite the jobs provided by these projects, the unemployment rolls contained more than 500 families during the darkest days of the depression.

Troubles in Europe and Asia changed the tempo of life and by December, 1941 volunteer groups had mobilized. Merchants provided space for the collecting and packaging of handmade socks, scarves, sweaters, hospital gowns and rolled bandages. War mothers established a canteen at the railroad station and a small USO club room welcomed servicemen at the American Legion Hall on weekends. Red Cross blood drives netted more than the area quota and parades, guest speakers and circus-like rallies publicized bond drives. Civic and social groups challenged each other to see who could "give" the most money or blood and school children vied with each other to win laurels for scrap paper or metal collection. A piece of the latter sometimes served as a free pass to the Saturday morning movie. Rationing encouraged everyone to walk instead of ride and to raise a victory garden and can vegetables and fruits. Everyone made sacrifices in time, money, or lives. Of the 3600 men from Warren County who served in the armed forces, 130 died.

The end of the war initiated an era of industrial expansion which provided jobs for urban and rural dwellers. Prior to 1940 the county's largest employers included Western Kentucky Teachers College, with a faculty of 125, Pet Milk with 140 and Honey Crust Bread with 80 employees; most businesses were locally owned and hired no more than several dozen workers. Although it is not certain that any large concerns considered a Warren County location, the prevailing local sentiment apparently opposed the introduction of heavy industry and its accompanying problems. In 1941, however, Union Underwear was invited to open a plant in Bowling Green and shortly thereafter General Electric's Ken-Rad located in town; during the war each hired more than 900 workers. Because of positive experiences with these new plants, post war officials worked zealously to attract more outside capital. They leased lots, planned an industrial park, and even suggested that businesses submit their lists of requirements. The hard work paid off. In the decades since the war, Warren County has attracted an impressive array of industrial giants.

Recent years have also witnessed an increasing appreciation in the area's architectural heritage and growth of cultural offerings. With leadership from Landmark Association, nearly 500 county structures have been placed on the National Register. A community orchestra, financed in part by book sales, provides an opportunity for players of all ages and skill to participate in making music and from the stage of the renovated Capital Arts Theatre school children and adults alike enjoy a feast of art, music, dance and theatre. Programs offered through the university further expand the educational horizons of area residents and thousands of local and out-of-state travelers visit the Kentucky Museum to learn about the past.

As it celebrates its bicentennial, Warren County offers top job opportunities, medical facilities, cultural and educational advantages as well as the best of town and country living. For those who occasionally long for big city amenities, Louisville (120 miles) and Nashville (70 miles) are easily reached by interstate highways. Mammoth Cave National park (25 miles), Barren River Reservoir (20 miles) and Nolin Lake (30 miles) provide recreational facilities. A 1982 publication that ranked the nation's towns and cities listed the Bowling Green area among the best places to live. Warren Countians agree.

Keywords

Warren County, Kentucky, Maps